Looted Art: What Indigenous Communities Lose When They Lose Their Art

In the concluding feature of our Looted Art series, Maya Garabedian examines how, beyond legalities and ownership, art removed from its home impacts its creators

Maya Garabedian / MutualArt

Jan 21, 2022

The question of who “owns” cultural art and artifacts is quite complex, with two distinctly different answers depending on whether ownership is defined by the possession of a work, or by the creation of it. Beyond the literal interpretations of ownership, time is an important determining factor. Work from long ago, looted or willingly sold, is often difficult to trace due to the limitations of a pre-industrial documentation processes — an inevitable sign of the times that has long been exploited by colonial powers. But, beyond the muddled logistics that can easily dominate conversations of ownership and serve as a roadblock to repatriation, there is a sentimental significance that is often overlooked. The cultural component of cultural art and artifacts is certainly a determining factor in ownership, as the term inscribes meaning that is crystal clear. The idea of art for art’s sake, introduced in the 19th century with the French slogan, l’art pour l’art, has influenced our perspective today — that art-making can be a hobby, with or without a clear intention, that it can be a profession, influenced by finances, and that the final product, the way it is exchanged and the reasons for doing so, the way it is displayed, by whom, and for whom, need not matter. The work may have a deeper purpose, be it political, religious, didactic, and so on, but whether or not it does is no longer a heavily weighted factor in determining ownership.

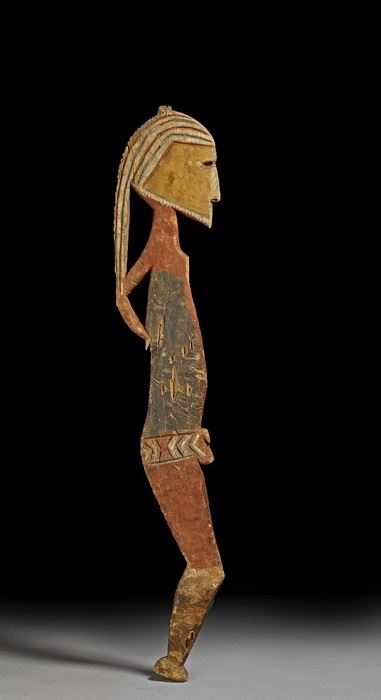

Artist unknown, Garden charm in the form of human figure (sokop madub), ca. before 1889, painted wood. Courtesy of the British Museum

Ownership of indigenous art is a quintessential example of how the modern-day value placed on art as an industry, displayed for its own sake, for the masses, and for a fee, has allowed possession of a work to overshadow purpose and cultural significance. Often, there is palpable irony in the ways in which looted works are exhibited, presented by the perpetrators of a painful historical experience leaving the victims to not only deal with the aftermath, but to do so without important relics of the time. One particularly salient example is an instance at the British Museum in London, unsurprisingly so, as the world’s largest receiver of stolen goods. In 2015, the British Museum held an exhibition entitled, “Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation,” which focused on 60,000 years of cultural art of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. In a lineup that was perceived as tone-deaf by many, looted objects from the museum’s own collection sat alongside contemporary works that addressed indigenous protest movements, reckoning with tragedies of the past and difficulties of the future. However, the looted works were directly related to the tragedies and difficulties in question — the people and events that gave this ancient civilization something to endure in the first place.

Artist unknown, Aboriginal shield, ca. 1750-70, red mangrove with white kaolin. Courtesy of the British Museum

Among the works on display was the Gweagal Shield, stolen by Captain James Cook in 1770 after encountering Aboriginal resistance upon his arrival at Botany Bay. The shield has a hole through it, likely from shots fired by Captain Cook’s landing party at the Aboriginal people awaiting the incoming invaders. Additional looted works included Aboriginal bark paintings, which served as storytelling totems, fishing nets, baskets, and tools used by hunters and gatherers; ceremonial headdresses, dance equipment, and instruments; sculptures that were believed to protect the land; canoes, boomerangs, and more. While these stolen items have long been a part of the British Museum’s permanent collection, the historical weight and struggle for repatriation were impossible to ignore when many of the objects from the exhibition arrived in Australia after the show’s run. The works were briefly displayed at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra, before once again being stripped away from their origins and sent back to London.

Artist unknown, Moai Hoa Hakananai’a, ca. 1000-1200, basalt. Courtesy of NBC News and Peter Nicholls / Reuters

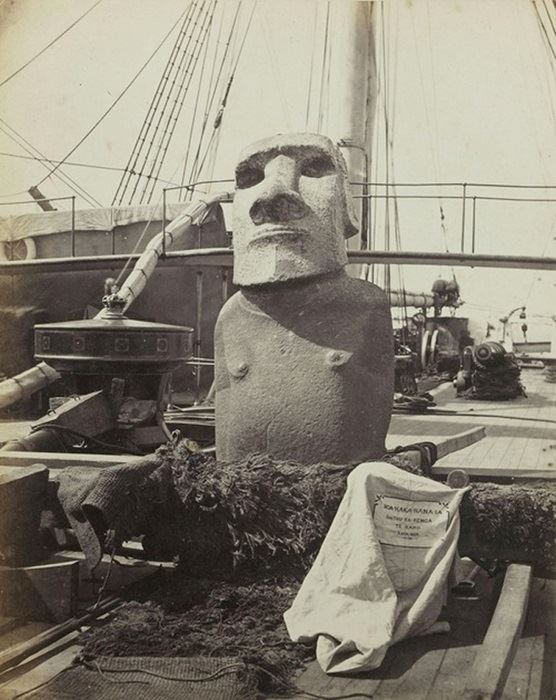

A more famous work taken from indigenous islanders and held at the British Museum despite pleas for repatriation is the Hoa Hakananai’a. A statue (moai) from Orongo, a ceremonial stone village on Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, is a flow lava masterpiece and considered to be one of the finest examples of Easter Island sculpture. Its relatively small size, clocking in at just under 8 feet, as opposed to the other moais that remain on the island and have an average height of 13 feet, allowed for its capture and removal. In 1868, officers and crew from the British Royal Navy ship, the HMS Topaze, dug out the Hoa Hakananai’a, dragged it from the Rano Kau volcano on a freight sledge, and floated it out to the ship on a raft. They also removed an additional moai, Hava, which is about 6.5 feet tall, although its condition is somewhat lackluster when compared to the breathtaking Hoa Hakananai’a.

Artist unknown, Moai Hava, ca. 1100-1600, volcanic stone. Courtesy of the British Museum

Moai Hoa Hakananai’a is the most visited, photographed, and studied moai of Easter Island, with millions of visitors each year, while paradoxically being held off the island. Not only would the statue’s return draw more people to the land of origin, witnessing the piece in its intended context, but it would have a meaningful impact on the indigenous community to which the moai hold special powers. Taken from Rano Kau, unlike the majority of moais which come from the quarries of a different volcano, Rano Raraku, the Hoa Hakananai’a is unique, especially with its intricate engravings and unusual features. The Hoa Hakananai’a is believed to not only be a beautiful example of the religious syncretism of the time, but a symbol of a vibrant indigenous society before it fell at the hands of colonialism, from diseases, to slavery, to seizure of land, goods, and art. Translated to mean “the stolen or hidden friend,” the moai’s spiritual significance remains today. It is believed that the spirit of the ancestors is held in the moais, and their return home will restore welfare to the island. The moai is seen as a living being, a protector.

Artist unknown, First photograph of Moai Hoa Hakananai’a aboard the HMS Topaze, 1868. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

In the tail-end of 2018, the delegation of Rapa Nui visited the British Museum and shared some powerful words that adequately encapsulate the reason cultural artifacts deserve to be returned. Governor Tarita Alarcon Rapu said, “We are just a body. You, the British people, have our soul.” Anakena Manutomatoma, who serves on the island’s development commission and was present in the bid for repatriation, explains it further: “We want the museum to understand that the moai are our family, not just rocks. For us [the moai] is a brother, but for them, it is a souvenir or an attraction.” The emotional toll and sentimental value of cultural art and artifacts is not only deserving of recognition, but of influence in the repatriation process.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page